By Vivian Marie Lewis, McMaster University

They come from all over the world to see, touch and read the originals of tens of thousands of letters, to study boxes of drafts and revisions of his ideas and mathematical equations, to understand his complex personal relationships and to explore the commitment to peace and opposition to nuclear weapons that landed him in jail more than once.

Visitors love to look at the wiry thinker’s easy chair and imagine what he must have been pondering as he sat there.

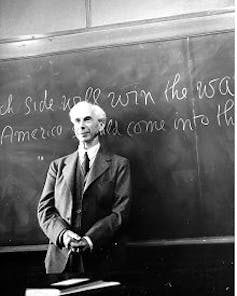

These, together with a Nobel Prize for Literature, a desk, a tweed suit and a trademark pipe, were the belongings of Bertrand Russell, modern philosopher, social critic, mathematician and anti-war crusader who died in 1970 just a couple of years short of his 100th birthday on May 18.

Canada’s McMaster University obtained Russell’s vast archives 50 years ago this year, and the parade of scholars who continue to use them affirms that his ideas are at least as relevant as ever — perhaps more so today, when the threat to world peace seems so grave.

How can the ideas of a man who started teaching at the London School of Economics in 1896 — and who corresponded with Jean-Paul Sartre, Ho Chi Minh, T.S. Eliot and so many others, and lived long enough to protest both the First World War and the Vietnam War — still be so meaningful?

Russell remains pertinent

A few years ago, I was home with my teenaged son, Michael. He was supposed to be working on an essay for a high school philosophy course, but I could hear the distinct sound of laughter coming from his room.

I asked him what was so funny, and was happily surprised by his answer: He was reading Bertrand Russell’s History of Western Philosophy and found Russell’s wry commentary very funny.

If I had ever needed affirmation that Russell remains pertinent, I certainly had it, though few would doubt the value of a life’s work that generated more than 4,000 publications on such disparate topics as truth, geometry, morality, politics and the future of humanity.

Not even imprisonment could stem Russell’s spirit or the flow of his ideas. He managed to write his Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy while incarcerated for pacifism during the First World War, and even sent the warden a copy to thank him for the opportunity.

Russell’s papers and ephemera are gathered in the McMaster library’s William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, where his desk and chair and more than 3,000 books from his personal library are shelved in the same order in which he kept them.

The fact that these archives ever reached McMaster is testament to the vision and audacity of the chief librarian of the time, William Ready, who, with the firm backing of McMaster’s president Harry Thode, brought the load of trunks, boxes and cabinets across the Atlantic from Wales after outbidding serious international competitors.

Opposed the Vietnam War

Ready’s chances at securing the archives had been boosted by Russell’s opposition to the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, which dampened the enthusiasm of potential American buyers.

Ready was a literary adventurer and his coup with the Russell archives came as he also managed to land Anthony Burgess’s typescript of A Clockwork Orange and extensive collections of rare books that today comprise an internationally renowned collection.

Thode, a world-renowned nuclear scientist, had recently secured a nuclear research reactor for McMaster’s campus and, as university president, was eager to balance that scientific triumph by securing a research asset of similar importance for the humanities.

Half a century later, the reactor continues to facilitate scientific discovery and to provide valuable medical isotopes while, across campus, the Russell archives remain a magnet for scholars the world over.

Russell student still tends to collection

Amazingly, the Russell archives and its supporting collections continue to be under the able and conscientious care of a man who had worked for Russell himself.

Ken Blackwell, a Canadian, was a young man when he went to work for Russell — a philosopher in his own right and a devoted student of Russell who landed a job organizing the Russell collection for eventual sale.

When Ready imported the collection, Blackwell came with it, and he stayed. Today, he likes to joke about emerging from one of the packing boxes. He spent the rest of his career on those papers and, in his retirement, continues to do so as a volunteer.

In addition to their own research value, Russell’s archives have helped McMaster draw other collections, including that of McMaster’s own peace advocate and cultural critic Henry Giroux, who carries Russell’s torch into new battles against ignorance, violence and unchecked corporate and political power.

This year, as we celebrate the half-century anniversary of McMaster’s stewardship of the Russell archives, the university library is giving them a new home.

Together with the Bertrand Russell Research Centre, the Russell archives will reside in a specially renovated facility on the doorstep of campus in a lovely older home at the edge of the historical Westdale neighbourhood in Hamilton, Ont.

![]() There, scholars will be able to continue their investigation of the archives, finding fresh wisdom and inspiration to carry into our ever-changing world, which needs Russell’s principled guidance and wide-ranging intellect more than ever.

There, scholars will be able to continue their investigation of the archives, finding fresh wisdom and inspiration to carry into our ever-changing world, which needs Russell’s principled guidance and wide-ranging intellect more than ever.

Vivian Marie Lewis, University Librarian, McMaster University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.